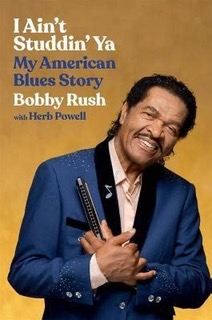

Bobby Rush Autobiography- I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya

Bobby Rush Autobiography – I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya

By Randy Murphy

“All bluesmen are optimists,” Bobby Rush explains in his splendid new autobiography I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya.” “You almost gotta be. The next record. The next big gig. And maybe this old bumpy dirt road will turn into a freshly paved easy street.” I’m not sure I’d limit this sentiment bluesmen (or women) alone but the comment is telling and Rush easily qualifies as a classic example of someone who takes the sanguine view on just about everything. While the road to stardom that many of his mentors and contemporaries—Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howling Wolf, Little Milton—followed eluded Rush, he seldom allowed it to discourage his confidence or diminish his love of this music. And now, with two Grammys in his pocket and a newly-minted autobiography in bookstores, Rush’s road seems finally to have received some newly laid and richly deserved blacktop.

I’ve read more autobiographies of musicians, writers, artists, and politicians than I care to admit, and the one theme common to nearly all of them is that of obsession. At some point in the narrative, a passion, sometimes bordering on mania, grips the author, and from that point he is bound to its whims and consequences and heartbreaks. Rush’s story is no different.

Bobby Rush, whose birth name is Emmett Ellis Jr., begins by taking us back to Circuit, Louisiana during the decade before World War II. There, growing up one of ten children in a tiny town that, in his words, was “like a million other[s] in the rural South. It was just a road with a sign,” Rush’s fixation with music began when his father “pulled out of his pocket a dull silver harmonica.” His vivid description of the effects his father’s playing had on Rush will sound familiar to anyone who’s been gobsmacked by music: “On his rock-solid knee, my mouth hung wide open. I was astonished. I could do nothing more than to stare deeply into his brown eyes and listen to the greasy yet melodic sound coming out of the harmonica.” That’s how it starts, isn’t it? Once music chooses you, there’s not really too much one can do about it but let it live in and through your life. To quote Hooker, “let that boy boogie-woogie.”

Through both his music and in his memoir, Rush displays his abilities as a natural storyteller. His prose is rooted in a rural, Southern vernacular—conversational, informal, full of those colorful and clever colloquiums that add spice to our language: “shotgun house,” “smack-dab,” “pig-in-a-poke,” and he’s structured the chapters his book, some barely spanning half of a page, as a series of anecdotes, vignettes, reflections, and commentaries. But oddly enough, it hangs together due to Rush’s ability to maintain twin narratives of survival and redemption throughout the books’ various scenes and episodes.

This memoir is also often hilarious, whether Rush is describing how to create a false mustache from burnt matchsticks (helpful if you’re a twelve year old looking to crash an adult music club) or the proper way to run a “mule hustle,” essentially stealing a mule a couple times a week and then returning it to its owner for the bounty:

We stalked through high brush to the farthest end of Mr. Yuke’s mule corral. Hunched down like commandoes invading enemy territory, we knelt real low and cut that fence. We then clicked out tongues to draw a mule near, carefully looking around to make sure we weren’t seen. That old mule walked out. Alvin put a rope around his neck while I sealed back the fence by twisting the wire together. Taking the long way around, we were soon at Mr. Yuke’s door [and] he thanked us and gave us a dollar. We did that a few times a week. It wasn’t right, but we didn’t feel it was too wrong, either—with the wealth they [White land owners] had inherited and all the Negroes they had working for scraps.

Of course, anyone growing up or writing about life in the Jim Crow south will run headlong into questions of race—it’s simply inevitable, but Rush deals uniquely with the vile prejudices of the era by often viewing them through a musical lens. It’s this lens that allows Rush to place all the racial turmoil and wretched injustices into a larger context. Here, he uses the idea of “naming” to examine the cultural appropriation of Black music by White culture.

Daddy taught me biblically, through the Old Testament, that it was an act of superiority to name something. And it was an act of submission to take the name shelled out to you. I know history gets written by the powerful. And white folks were trying really hard to take what we’d cooked up and make it theirs. But the fact remains that the only thing that white folks did to create rock ’n’ roll was Allan Freed giving it the name rock ’n’ roll. And with white folks being in power in every layer of American society, there was an immense power in the naming.

So even today, I hear their voices screaming in my memories and howlin’ from the heavens: the voices of Ike Turner, Big Joe, Little Richard, and they all are shouting the same thing: “It ain’t motherfuckin’ rock ’n’roll! To hell with that. It’s rhythm and blues.”

This is a tough truth to read. I always knew—well, suspected anyway—that much of the music I grew up listening to, rock, blues, most of the jazz, was not really mine in the sense that it didn’t emerge from the experiences of my ancestors. Rush validates that knowledge without belaboring the point. Of course, that does not diminish any of our appreciation for this music or our love for it, but Rush does us a service by placing the origins of the music squarely within its proper context.

In the end, this is a delightful book written by a man who endured much during the course of his life, but who made it out clean on the other side.